Part 2. Djanet

Crew change and desert preparations | The explosive legacy of the Franco-Algerian War

We are in Djanet for 48 hours, picking up 5 more crew members at the airport, shaking out the sand and preparing for the next leg of the journey into the southeast corner of the Tassili n’Ajjer park and the Tadrart Rouge, within easy bazooka range, we joke, of the borders with Libya and Niger.

We will need to be self-sufficient for 12 days and begin filling tanks and jerry cans with fuel and water and loading up on fresh food. As I arrange supplies in the Defender, a young woman introduces herself. She is an English teacher in Algiers visiting her family in Djanet. After a pleasant exchange, she offers us a tin full of cookies she had just made. I give her one of my baksheesh Swiss chocolate bars. She accepts it with obvious pleasure, but her mother calls her over and whispers something in her ear. She shyly asks if I have “medicine against headaches”. I had read that this was a common request in the remote places of the Sahara and had come prepared with extra boxes of paracetamol.

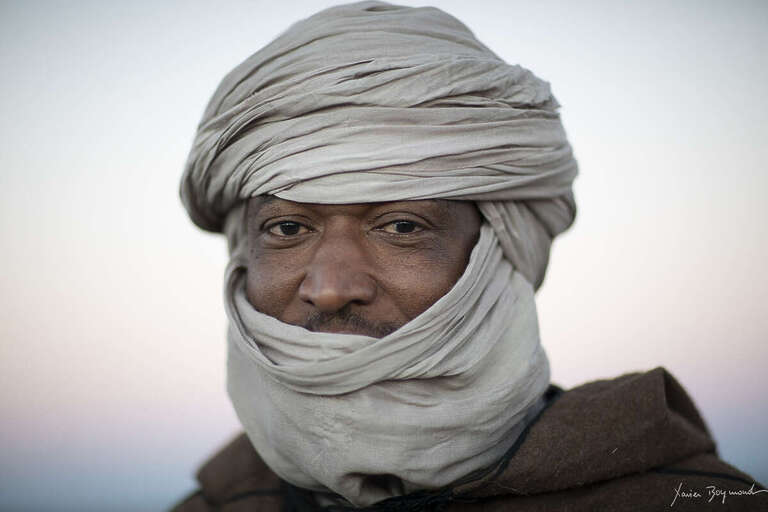

We say goodbye to Amastan and meet our new guide for the dunes, Otchi, also a Tuareg, with whom our group’s leader has worked before. He is stout and solid, with a toothless smile and eyes baked into a permanent squint. He is wearing dark brown pants and a dark brown coat, and unlike most Tuareg we meet, he does not cover his head, revealing a crown of soft thinning curls. Otchi grew up here and has been exploring the desert on moped since he was 14. He is passionate about the region’s rock art and has guided teams of archeologists to locate and document the thousands of sites scattered over thousands of square kilometers of difficult terrain. In a light voice that is a surprising contrast with his rugged appearance, he greets us and we go over our plans for the next 2 weeks. As our Swiss convoy leader goes over logistics with him, we are discretely amused watching the immiscible interplay of Swiss precision and the ‘This is Africa’ reality of travel here, with Otchi’s gentle ‘Insha’Allah’ (if Allah wills it) following every Swiss plan announced.

At the hotel, we meet Amal, a small, energetic Franco-Algerian woman hired by the hotel to advise them on ways to improve their services for European travelers. She tells us that it is not an easy task because even though they have asked for her help they believe she is being condescending and stubbornly resist any of her suggestions. She shakes her head sadly, looking out over carefully-tended gardens and whitewashed walls perched above large rock outcrops and sand dunes behind the hotel. “There is such potential here,” she says, sweeping her arm across the horizon. “But the government and military make things too complicated for tourism to grow.”

Algeria is both blessed and cursed with oil and gas reserves. The 10th largest country in the world, Algeria is ranked 11th in the world for its natural gas production, making this industry the backbone of the Algerian economy. But Algeria is also surrounded by difficult neighbors with unstable governments, jihadist groups, black-market bandits, human traffickers, and thousands of kilometers of remote borders nearly impossible to patrol or secure. Amal tells us that the government is also under pressure from ‘outside forces’ to ensure that Algeria’s vast resources don’t fall into the wrong hands. Because of its oil and gas reserves, Algeria did not rush to develop its tourism sector after independence as its Maghreb neighbors Morocco and Tunisia did, and tourism is still a double-edged sword for Algeria. Many would like the income that tourism would bring while others fear the destabilizing influence that an influx of strangers with strange ideas might have on the complex and fragile stability of the country. We feel this sentiment percolate through our conversations with several Algerians we speak to, who warmly welcome us but also make it clear that we are their guests, not their clients. I pay close attention to the way the women are veiled as we enter each new town to know how much of my face I can leave uncovered. We speak a few words of Arabic and avoid launching into conversations in French, the former colonial language that only the older generation speaks fluently now.

I arrived in France in 1998 when France was just beginning to come to terms with what happened during ‘the silent war’ between France and Algeria, only officially called a war in 1990. For France, Algeria was simply the southern territory of the French empire, with Charles de Gaulle declaring “All French, from Dunkerque to Tamanrasset”.

As military records were progressively declassified in the late 90s, articles and documentaries tried to make sense of it all. While French soldiers would readily talk about their experiences during World War II or, more reluctantly, in French Indochina, few would talk about what happened here in Algeria between 1956 and 1962.

What began with the French occupation of Algiers in the 1830s in an attempt to stop Barbery pirates from disrupting French trade in the Mediterranean unfolded over the next 130 years like a Greek tragedy.

Under the leadership of an unlikely hero, local tribes were organized into an Assembly by Abd el Kadar, a 25-year-old scholar and son of a respected religious leader. France, only interested in the Mediterranean coast at that time, recognized Kadar and his Assembly as the sovereign authority over the center and west of the country. Kadar would be hailed around the world for his respect for human rights, humane treatment of prisoners of war, and protection of Christian communities during conflicts, earning him praise from Abraham Lincoln and the founders of a new American town in Iowa named in his honor – Elkadar.

Peace was short-lived and France soon changed its mind about not wanting the rest of Algeria, leading to massacres and the beginning of multiple exiles and returns of el Kadar. Local tribes fought against the new wave of French attacks with a combination of light infantry and black magic, their sorcerer’s invisibility spells giving them blind courage to rush boldly into massacres. To stem the bewildering attacks and subsequent bloodbaths, the French government called on French magician Jean Eugene Robert-Houdin (better known as Harry Houdini) to prove to the tribes that French magic was stronger than Algerian magic.

A wave of colonialization followed, with the French authorities recruiting colonist from all over Europe with promises of land and a mild climate, while glossing over problems of malaria, dysentery, and the hostile local population. They tried to win over colonists headed to America and to appeal to newly displaced exiles from the Alsace-Lorraine region after the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, but with limited success. In the end, nearly half of the “French” colonists came from other parts of southern Europe – Spain, Malta, Italy, Sicily. The French authorities also decided that an easy way to create new French colonists in Algeria was to naturalize the 25,000 native jews of Algeria, instantly destroying the fragile entente developed over centuries between the local Jewish and Muslim communities.

Over the generations, this mix of colonists (called the pieds noirs, or black feet by the French) created their own dialect and culture, and in some areas, something close to the paradise that was promised by the French committee for immigration. Fertile areas in the north produced numerous crops, with farmers eventually concentrating their efforts on the more profitable vineyards and orange plantations. One particularly successful orange plantation and the ingenuity of a Spanish colonist gave birth to the famous Orangina soft drink in the village of Boufarik, ‘the pearl of colonialization’. Generations were born here and knew no other home, making this jewel of the Mediterranean nearly impossible to give back when the time came.

World War II showed the Algerians that France was vulnerable and the publication of the Atlantic Charter by Roosevelt and Churchill spread the notion of auto-determination that led to the 1943 Manifest of the Algerian People, with young pharmacist-turned-politician Ferhat Abbas calling for an Algerian Nation. Many French writers, politicians, and intellectuals of the day sympathized with the Algerians. De Gaulle suspected that the Americans were fomenting rebellion in an attempt to claim Algeria for itself after the war. French-Algerian tensions came to a head in 1954 when the French felt the need to violently crush notions of Algeria independence following their recent defeat at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam that marked the end of the colonialism experiment there.

It was during this period that the French war college perfected a new style of warfare, called by others who would later use it in South America and Vietnam as ‘The French Doctrine’. This strategy consisted of cutting off guerilla soldiers from support and assistance of the local population by attacking villages suspected of sympathizing with the enemy, along with liberal use of torture to strike terror into the enemy. The Algerian factions fought back, terror-for-terror, attacking colonists and soldiers alike with a war carried out in the shadows of towns, businesses, and homes. These are the stories no one wants to talk about and we are only just beginning to get a blurry picture of the scale of the horror today.

In 1959, standing up against strong opposition at home and among the colonists, De Gaulle declared a progressive transition to auto-determination for the Algerian people, leading to the Evian Accords in 1962 and the forced evacuation and resettlement of 800,000 pieds noirs and Algerians who had fought for the French. France is still today trying to cope with the consequences of this failed experiment and repatriation of the colonists, considered by many French simply as Algerian immigrants, with increasing tensions fueled by populist propaganda and anti-immigration sentiments growing across Europe.

But sadly, our Greek tragedy does not end here. In the Evian Accords, there was a clause in the agreement kept secret that gave the French the right to use the southern Sahara region to test nuclear weapons. Between 1960 and 1966, 17 nuclear tests were carried out, not in the far-flung barren desert areas, but near the towns of In Ekker and Reggane along what is now the Trans-Saharan Highway, and our return route home. Thirteen of these detonations were carried out in underground facilities below the Hoggar mountains. The first of these explosions was four times stronger than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima, leading to the destruction of human and animal life and the contamination of thousands of kilometers of land and water near the site. When the French left the zone in the late 60s, they buried contaminated material in the Sahara. The exact nature and location of these contaminated materials is still classified today despite renewed calls from the Algerian government to declassify the information. See also Part 5 of this article for more information about the French nuclear programme in Algeria as we drive the Trans-Saharan Highway past the testing grounds.

I am deeply affected by the atrocities of my adopted homeland during this dark period, and ask friends how I can tell this story without making the French appear to be monsters. The necessary coming-to-terms process has only begun for the French government and its people, and we must hope that in time we can view this period through a more comprehensive lens that will allow us to learn from the lessons of the past and find something like reconciliation.

I am haunted by a phrase from French writer, politician, and adventurer Andre Malraux: “You are not what you show; you are what you hide.”

We avoid talking politics with the Algerians we meet, but I mention a new rise in tensions between the French and Algerian government to Amal to see if she will share her perspectives on the past and the impact it has had on her life. Amal simply frowns and shrugs. “It wasn’t you, it wasn’t me. What can we do? We just have to move forward.”